If you’ve spent any time in education over the past few years, you’ve likely sat through a keynote speaker at a conference or a breakout session on a PD day where someone shared an image of a classroom from 100 years ago and a classroom today. Maybe you saw a picture that looked like this:

The point is painfully obvious. Despite more than 100 years of innovation in the world around us, school has changed very little. We have substantially greater resources and far superior technology at our disposal, but the “what” and the “how” of learning for our students largely hasn’t changed. We share these pictures as a call to arms; a stark visual which we hope will prompt change. But they don’t.

I’m convinced that the reason we don’t see change isn’t because we don’t have the tools, or the innovative leaders necessary to make the change happen. Instead, I believe we aren’t innovating effectively in schools because we haven’t correctly identified the problem. More specifically, while we know in a general sense what is wrong – that today’s classroom looks strikingly similar to classrooms from 100 years ago – we haven’t correctly identified the forces we must leverage in order to initiate and sustain meaningful change. We fall for quick fixes like new tech tools, flashy curriculum, and new instructional platforms, rather than attempting to address the root causes of our current stagnation.

To make meaningful changes we need to start by building a new foundation to support a modern view of teaching and learning. Below I outline the 6 factors that I believe we must leverage to create meaningful change in our schools.

1. Overcoming the Cult of Shared Experience

One day, after a routine check-up, Sarah received a call from her doctor, Dr. Rosenberg. The voice on the other end of the line said flatly, “Sarah, there is something that’s come up in your blood work and I’d like to speak with you about it. Can you come to the office tomorrow?” The next day Sarah found herself back in the Dr. Rosenberg’s office – palms sweating, stomach in knots – as her mind drifted to the worst case scenario. Just then Dr. Rosenberg entered the room and sat down slowly across from Sarah. He leveled a soft look in her direction, as if trying to take some of the weight off of what he had to say. “Sarah,” Dr. Rosenberg said, “I’m afraid I have some bad news. Your blood work indicated the presence of cancer in the blood.” Sarah’s mind raced, attempting frantically to comprehend the way her life has changed in a matter of just a few seconds. As she began to think about her family and what this diagnosis would mean for them, she was suddenly wrenched back to reality by Dr. Rosenberg’s voice. “There is some good news here,” Dr. Rosenberg said. “A recent study of an experimental therapy has shown great success in treating patients with a diagnosis similar to yours, Sarah.” For the next thirty minutes he went on to detail the treatment plan and timeline. As Sarah left the office, she was filled with emotion. She felt scared, yet at the same time hopeful due to her new experimental treatment plan.

Sarah’s story is, unfortunately, common. In fact, odds are, you or someone close to you has had a similar experience. According to many estimates, there has been as much as $500 billion spent on cancer research since the 1970’s. Yet, despite all the time and money spent on cancer research, the mortality rate has changed little in the past 40 years. So why would Sarah be optimistic about her new treatment plan? Why should she trust Dr. Rosenberg when he tells her that there is good news?

I’m convinced that a big reason for Sarah’s optimism was her trust in Dr. Rosenberg, based on a lack of shared experience. In other words, Sarah trusts the “expert” (Dr. Rosenberg) because she herself is not a doctor. She doesn’t have the academic knowledge, background experience, or understanding of the human body needed to develop possible treatment plans. She trusts Dr. Rosenberg when he says that the experimental treatment plan is good news, in part because she lacks exposure that might indicate otherwise. This lack of a shared experience is the same reason we take the advice of our financial planner, or the plumber diagnosing a leaky faucet at our house; we seek out their expertise and opinions because we lack the experience needed to develop accurate opinions of our own.

Education, on the other hand, is one of the few shared experience that virtually every member of a society will share. Through our experience we develop our own opinions about what education is and what it ought to look like. This expectation largely reinforces a view of learning that is typically grounded in left-brain, analytical thinking provided in an assembly line model. That is, we expect the learning process to be defined by a set of facts and figures, which are presented by the teacher and mastered by the student, and are accounted for through a standardized test. That’s the way we did it. That’s the way our parents did it. That’s the way it ought to be done.

Put another way, our shared experience in education (whether a positive or negative one) carries with it a certain element of nostalgia that makes change exponentially more difficult. Take Sarah for example. She accepts that the “new” experimental treatment plan will likely have a better result for her, at least in part because she doesn’t have any other experience by which to form an opinion. She never experienced the “old” treatment plan, and thus, she has no expectations for what a treatment plan for cancer should entail. The problem with shared experience, at least in the case of education, is that everyone becomes a pseudo-expert with strong opinions.

So how do we counteract the limitations posed by our own experiences as students? For starters, we need to begin to cast a new vision for education. It is important to note that this isn’t a one-time event, but rather an ongoing process of informing and exposing our communities to the realities of the working world, the research around teaching and learning, and the impact these two things have on determining what instruction should look like. There are a variety of ways to accomplish this, but I would suggest that the best path is to be varied in your approach. After all, each of the strategies listed below will have a different target audience. Like in fishing, the more lines you have in the water, the better your chances of success.

- Increase your social media presence – Social media is a great way to share educational research, innovative teaching and learning experiences, and article recommendations with your followers (think: parents and teachers). But, it can also be a great tool for connecting with like-minded educators. Not only can social media be a great platform for sharing your message, it can be a great tool for finding new articles, research and books that might help you along the way as well.

- Start a book study with parents – Engage your parents in reading and discussion around teaching and learning. Not only will this provide key opportunities for parents to engage with the school, but they can begin to partner in the dialogue and develop greater investment and ownership in the change process. There are a ton of great education related books that might fit the bill, but something more mainstream (like A Whole New Mind by Daniel Pink) might be a good place to start.

- Engage your working community – Sometimes the best way to convince our communities about the need for change in education, is to engage our local working community. Hold a career panel, or invite community members to give feedback on student projects that might be related to their field. Engaging the working community has three big upsides. First, it creates an opportunity to expose students to the world of work, making their learning more relevant. Second, it creates an opportunity to target specialized resources in your community that likely won’t cost you a dime. Third, it serves to highlight what skills are needed in today’s careers – namely, the ability to communicate effective, work collaboratively and to creatively solve real-world problems.

2. Confronting the Relevance Gap

One of the curious components of education is its ability to remain insulated from the world around it. Even a cursory look at the society around us highlights how interconnected business, technology, healthcare and a host of other industries are. Even the slightest innovation or improvement in one sector drives swift innovation and change in another. It’s not surprising then that we see exponential rates of change every year. Yet somehow, as if immune to the world around it, schools rarely change. Take technology as an example. I remember going into a Radio Shack store fifteen years ago. At that time you could find rows filled with cordless phone batteries, CRT televisions and film cameras. Today, Radio Shack is on the verge of going out of business. Furthermore, I think you’d have difficulty finding even one of the items listed above at your local electronics store. Why? Because technology improves, tastes change, and these things drive rapid innovations in product development.

Now consider another example. Consider the holy grail of teacher shopping: Lakeshore Learning. I would venture to guess that over the same 15 year period I described above, the store (and more importantly its products) have changed very little. They still have the same classroom manipulatives, math and writing workbooks, and student learning aides. That isn’t a knock on Lakeshore Learning. It’s simply an observation about education. While we demand change in every aspect of our daily lives, we don’t expect the same from our schools. That, I’m afraid, is setting students up to be woefully unprepared for the jobs and social structures that will greet them upon graduation.

As educators, our role is as much about educating the students in our charge as it is to educate our communities about the disconnect that we all know exists between the “real world” and the accepted “structure” of school. When we acknowledge the difference, we can begin to target the gap, thus moving student learning into the real world. This change is tangible, and it’s powerful for students. Learning that is steeped in the challenges and technologies of today provide easy avenues to increase the meaning and relevance of learning for students – a key ingredient to increasing engagement. Real world challenges also help to provide a context for the learning of skills and content that is “on-time” for the task. Sounds great right? It starts with connecting school to the world of today, not insulating it from change. Below are a few ideas of how leaders can start to confront what I call the “relevance gap.”

- What’s the Problem? – If learning at your school is based entirely on content, you’ve already lost. Our students are ALREADY living in an era where “knowing” things is largely irrelevant, and it will become increasingly so as they age. Because of this, we need to focus on developing the skills students will need to think critically and to creatively tackle the problems of the future in this new knowledge economy. Leaders can start by helping teachers structure their learning around real-world problems. Project Based Learning (PBL) and Design Thinking provide key methodologies for approaching learning through driving questions that are relevant and meaningful to students’ daily lives, and may be a good place to start.

- Backwards Planning – I know, you’ve heard all about “backward planning.” But hang on, I’m not talking about a 5-step lesson plan. We need to go further out. Take a look at where we hope students will utimately find themselves after school: career. Leaders need to engage and connect with industries and careers in their communities to get a clear sense of what these employers are looking for in graduates. What are the growing needs? Where are today’s students falling short? Where are our industries headed? If you engage in these conversations you’ll hear a lot of the same answers. Employers are looking for people who can gather, synthesize and apply information in new and unique ways. They are looking for creative problem solvers. They are looking for people with excellent verbal and written communication skills. They are looking for people who can work well as part of a team. If we start with these realities as our north star we can structure learning in schools to match those needs. Here’s a hint: much of what our schools emphasize don’t typically develop these skills. Let’s change the game.

3. Recognizing the Stakes of the Game

In his book Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science, Atul Gawande talks about the paradox every surgeon faces in his/her work:

“In medicine, we have long faced a conflict between the imperative to give patients the best possible care and the need to provide novices with experience. Residencies attempt to mitigate potential harm . . . But there is still no getting around those first few unsteady times a young physician tries to put in a central line, remove a breast cancer, or sew together two segments of colon. No matter how many protections we put in place, on average these cases go less well with the novice than with someone experienced.”

(Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science, Page 24)

What Dr. Gawande describes in this passage is a paradox faced by doctors everywhere. When it comes to medical care, we all expect the most experienced physician, not a novice who is likely to make a mistake. This is especially true in cases that are high stakes, such as heart or brain surgery. Yet, we also recognize that practice is the only way to attain the level of expertise that we demand. For this reason, we are left with a challenging paradox. We know that practice is a necessary part of the process, yet nobody wants to be the guinea pig when stakes are high. The same can be said of education. We typically recognize that change is necessary, yet we stop short of making the changes we know we need.

If there is one thing people hate more than the idea of being a proverbial “guinea pig,” it’s the thought of their child being one. Our children represent what is most important to us, and we want what is best for them. If we agree that schools need to change in order to best prepare students for the future, we should be clamoring for something different. Yet, in the back of our minds, we struggle with the same thought: What if “new” isn’t actually better? What if “new” actually ends up being worse? The thought of possibly “ruining” the education of a generation of students with unproven methods is enough to make even the most ardent change agent take pause. We all want change, but we want it tested on someone else first.

As in the case of medicine, where the concept of practice need not be synonymous with with poor care, taking risks in school is possible without subjecting our students to detrimental consequences. Below are a few ideas for how schools can begin to develop an appetite for change in their own buildings and amongst their broader school community.

- Recognize the elephant in the room – I think the first step for any school needs to be an open recognition of the fears parents (and educators) face about the potential consequences of change. By recognizing the concern we validate the feelings of those around us and send a clear message that we are cognizant of the stakes of the game. From there we can develop a level of trust with our community, knowing that any change we make is thoughtful and measured.

- Do your homework . . . or not – Trying something new doesn’t mean taking a total shot in the dark. We can try things in school that we know will have a high probability of returning positive results if we keep ourselves up-to-date with current research in education and the working world. For example, the thought of eliminating homework in schools, an idea that would have been sacrilege only a few years ago, is readily being adopted by schools across the country. Why? A primary reason is that there is a growing library of research which provides tangible data that this approach works. Staying abreast of educational research can help to provide critical guidance for educators and reassurance for concerned parents that our trajectory is sound.

- Toughen up! – If we are honest as leaders, some of our reluctance to push for change comes from a sense of self-preservation. We want people to like us. We want to avoid criticism. We want people to tell us we are doing a good job. But when we look at some of the key figures of the last couple of centuries – Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, the Wright Brothers, just to name a few – we see that those who have contributed the greatest innovations have ALWAYS faced criticism along the way. We need to expect that this is will be part of the process and we need to embrace it. And, if you find that you have detractors, take heart. It’s probably a sign that you are on to something big. Keep going!

4. Cultivating Disruptive Cheerleaders

As schools have become larger and resources more scarce, the role of the principal has changed greatly. Today, the role of “principal” has become almost completely synonymous with “manager.” Our school leaders are often forced to spend more time managing schedules, discipline, mental health issues and finances, than they do the educational program of their campus. Moreover, many educational leadership programs at universities still spend a majority of course hours on managerial components (finance, school law, etc.) – further reinforcing the managerial understanding of what it means to be a “principal.”

To be fair, managerial duties are a crucial part of the role of a principal. A school that doesn’t follow the law or manage financial resources appropriately won’t last long. However, the job of principal has to be more about the leadership of teachers and students than simply managing the day-to-day elements of school. If we are honest, our administrative office staff probably does a better job of managing the day-to-day elements of our campuses anyways.

So what should a principal be if not a manager? An effective school leader in today’s schools must be both a DISRUPTIVE force and an exuberant CHEERLEADER. These certainly aren’t the only important traits a leader must have. Still, being disruptive and being a cheerleader are often two traits that are cast aside in favor of more traditional, assertive characteristics. Despite this trend, I think these are the two most critical traits needed to assure the success of our schools and our students.

We know that change is needed. And, because we also know that as human beings we often resist change, even the most well-intentioned educator can fall victim to routine and convenience. When people ask me what I do for a living, I often will tell them that I am a “Chief Disruption Officer” rather than a principal. Not surprisingly, I get some strange looks. We are conditioned to think of disruption as a negative – like the “disruptive” student in class. Yet, in truth, this is exactly what schools NEED. Weston Kieschnick has this to say about schools:

I love this quote because I think it says so much about the nature of education. If left to our own devices we will almost always default to structures and content that allow us, as the adults, to remain comfortable. In other words, we do what we have always done because that is what is both easiest and most likely to deliver a predictable result. BUT, that isn’t what we signed-on for. We signed-on to help prepare kids for their future, not to wed them to our past.

Cesar Morales, the principal of Sage Creek High School in Carlsbad, California once explained the nuances of this style of leadership to me this way:

Imagine that you have a long table with a bunch of marbles on one end of the table. Now, imagine that your job is to get all of those marbles from one end of the table to the other. You might think that all you need to do is pick-up one end of the table and allow the marbles to roll across, but you’d be wrong. If you do that you will likely lose more marbles off the side of the table than you will have marbles make it to the other end. Leadership is just like that. You are the person lifting the table, trying to get the marbles to move to the other end, sure, but the key is how you balance the table. What slight moves and corrections can you make to keep the marbles on the table, and moving in the same general direction? Each marble will take its own unique path, and will move at different speeds – you can’t change that. All you can do is make sure you keep all the marbles on the table and moving in the same direction. That’s leadership.

I love that explanation of leadership, because it highlights exactly how critical the balance of disruption is. If leaders are too heavy-handed with their disruption of the norm, they risk losing their team and alienating their community – like marbles falling off the table. On the other hand, if leaders don’t push for change and challenge the status quo, they won’t ever create the momentum needed to sustain change. We don’t want to do too much, but we need to do something.

This is precisely where cheerleading comes to the forefront. Encouragement is a critical, necessary counterpoint to disruptive leadership. Teachers, staff and students need to be constantly built-up and encouraged in order to feel safe enough to take the risks that our disruption demands. Without a trusting environment where risks and innovations are both supported and encouraged, many will simply default back to what they know. Where disruption is the spark that ignites change, cheerleading is the fuel that sustains it.

Finding the balance between disruption and cheerleading is a fine art. It’s a skill to practice and to hone. Below are a few ideas for how you can get the ball rolling at your own site:

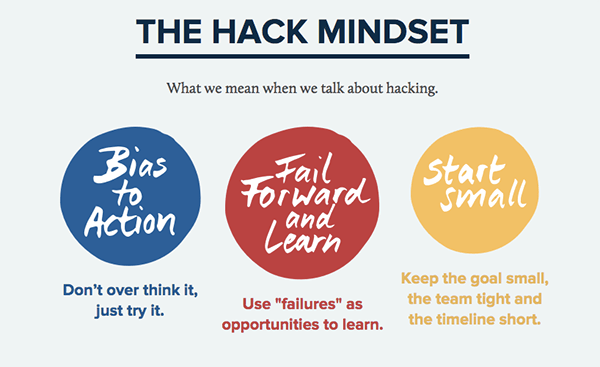

- Hack the System! – Change can be hard, especially when the change is something big. Give your staff (and yourself) the best chance of success by embracing the Stanford d.school approach to change: small hacks. Start with a small “hack” (or change) to something you do. Start with the lowest hanging fruit. Remember, you can’t do everything at once. Just do something. Then move to the next small hack. You’ll find that the successes, the momentum they create and the motivation of your team, will grow exponentially towards large-scale change. Want to know more about the d.schools approach to hacking? Check it out here.

- Get Out There! – You can’t effectively identify areas of needed growth, or disrupt the status quo of your school unless you are out WITH the teachers, students and families that you serve. In other words, you need to get out of the office! Imagine a mechanic trying to fix a car without inspecting it first, or a home appraiser assessing a homes value over the phone. It sounds ridiculous to think of, yet many administrators approach their schools this way. They pour over reports and data, consult with colleagues, and develop strategic plans – yet they spend precious little time in classrooms or engaging with students. If you want to make change, you need to know what you are changing. This past year I attempted to eliminate my office entirely – to force myself to work remotely, out on campus and in classrooms. While I couldn’t break away from the office all the time, being intentional about the shift was necessary to increase my time with students and change the way I saw my campus and its needs.

- Can I Get a Shout-out? – I mentioned previously that social media can be an important tool for leaders to connect with like-minded educators. However, social media can also be a great tool for highlighting examples of daring, innovative work on your campus. This public praise simultaneously does 3 things for your organization. First, it validates the work and risks that your staff are taking, thereby encouraging greater risk taking. Second, it helps encourage others in your organization to take similar risks, and models the process for them to do so. This may be just what is needed for someone else on your team to take the first step. Finally, it helps you establish the narrative or “brand” of your school around innovation. In that way, risk-taking and innovation become the rule, rather than the exception.

5. A Matter of Measurement

It’s no secret that standardized testing and the traditional system of grades and transcripts has a huge impact on what learning looks like in the classroom. Many of our classrooms are tailormade to disect test scores and drill students in hopes of eeking out a slight increase in standardized scores. In the film Most Likely to Succeed, they describe this system – the system by which traditional schooling is constructed – as a “game we have all agreed to play.” In other words, we focus on standardized testing, grades and transcripts, in order for students to get into a good college, and as the story goes, go on to have successfull careers. Fifty years ago, this trajectory would have been all but guaranteed. Today, it most certainly is not.

According to economists, approximately 44% of today’s college graduates are either unemployed or employed in jobs that they likely could have gained without ever going to college. There are certainly a myraid of reasons why this is the case, but a significant one has to be the exponential increase in technology that has allowed us to create more wealth with fewer employees. As computers can increasingly complete all sorts of traditional left-brain, analytical tasks, with greater speed and accuracy than humans, the required “skills” for success after college are changing. Traditional approaches to assessing proficiency, may not be measuring what matters most in this new economy.

Colleges are increasingly recognizing this as well. Consider that more than 700 4-year colleges in the United States (including prestigious schools such as the University of Chicago and Wake Forest University) have become “test optional” schools. That means that traditional SAT/ACT scores are not required for consideration for admission. Put another way, colleges are beginning to formally recognize that the “test” isn’t necessarily an accurate predictor of college readiness or longterm success. Consider also that employers are increasingly demanding more creative, right-brain characterisics from their workers. According to the World Economic Forum, the top ten skills that will be most desired by employers in 2020 include things such as “creativity, emotional intelligence, and cognitive flexibility.” These abstract soft skills are notoriously difficult to measure in standardized formats.

All indicators point to a dramatically rising tide that will change the “game” of school for our students in the not so distant future. The question then becomes how to leverage the current system in order to place value on those things that we know will be important in the future – despite the fact that they are not tested today. What we measure matters, and says everything about what we value most. So how do we begin to place greater value on the soft skills we know students will need, in a system where standardization is still king? Below are a few ideas for how to get the most out of your students in a standardized world.

- This is Football, Not Basketball – When we talk about measurement, we have to address a key question: Is it possible to emphasize both high standardized achievement scores as well as innovative soft skills, or are they mutually exclusive? My answer: maybe. Let’s say that you trained and practiced for years to play football. Now imagine that you decided – one day – to play basketball too. Does your work at being a better football player make you any better at basketball? Possibly. There are probably some elements of your football workouts that would pay dividends in basketball as well, such as cardiovascular endurance and strength training. But, in general, the skills and knowledge required to be great at basketball aren’t the same skills and knowledge needed to be great at football. Standarized test achievement and soft skills work that way too. While efforts to focus on creativity, communication, collaboration and critical thinking (the 4 C’s) may result in a better set of skills that may have a moderate impact on student abilities in a testing situation, the emphasis on one does not always translate to success in the other. We need to recognize that as a starting point if we want to get anywhere with the question of what to measure.

- Expand the Lens of Achievement – Another critical thing for educators to do, aside from acknowleding the complicated relationship between standardized testing and creative soft skills, is to expand the definition of student achievement at the site level. Educators can do this by providing opportunities for students to reflect on, and showcase, their work. Digital portfolios, exhibitions of student work and the use of rubric scoring to evaluate progress are good first steps that can begin to expand the definition of success for students. In addition, it also begins to elevate non-traditional learning dispositions alongside more traditional aptitudes.

- Become a Jedi Master – I think leaders (and everyone really) can learn a lot from Star Wars. Luke Skywalker never took a standardized test to prove his proficiency in his use of the Force. Luke Skywalker became a jedi by demonstrating his mastery in real-life situations. In other words, he demonstrated and displayed mastery by his body of work. We would be wise to treat learning the same way. Don’t focus on students demonstrating skills and knowledge in a finite way at a set time. Instead, provide learning experiences that allow students to revise over time and demonstrate mastery through their completion and exposition of high quality work.

6. The Narrative of School

School is a lot more like a Fortune 500 company than we often recognize. For all of our talk about learning, standards, content and proficiency, schools are as much about branding and sales as anything else. Businesses recognize the importance of narrative and branding as a key element to driving sales and the success of their organization. Effective storytelling draws interest, inspires loyalty and creates emotional bonds.

A compelling narrative is as important for schools as it is for any business – yet often schools overlook the value in telling their story. I often tell other educators: “There is a story being told about your school, whether you like it or not.” As a leader I believe you have only two choices when it comes to the story of your school. Choice number one is to embrace the importance of telling your story in the community, and to take an active role in the telling. When we do this we have a unique opportunity to determine what the message is, and what our focus will be. We can craft the story around what we determine to be most essential. Option number two is to ignore the importance of storying, and to convince ourselves that we have more important things to do. When we do that, we allow others to tell our story . . . and often it isn’t the story we want told. As George Couros says in his book The Innovator’s Mindset:

That is precisely the power (and the importance) or telling our story. In addition, stories are culture forming. Much like traditional folktales and stories have helped to establish and sustain cultures throughout history, our ability to effectively tell our story today will have a huge impact on our ability to firmly establish and perpetuate the values we have for student learning. In other words, the story helps to drive the outcome. What we see, hear and experience on a regular basis shapes us. So how do we shape our school communities? Below are a couple of ideas of ways to start.

- Social Media . . . Again – You knew it was coming, and hopefully by now you get the point. Social media is a critical tool for telling your story in short, informative, and visual blasts. Take pictures or videos of the great work happening on your campus. Highlight teachers who are taking risks and making waves. Share resources and ideas that are challenging your thinking about teaching and learning. Whatever you do, be sure to use redundancy with your message – twitter, instagram, facebook, a blog – the more platforms you engage, the more people you will touch. Hint: Don’t forget a #hashtag to help document the journey. #maglionpride.

- Empowerment is the Best Marketing Campaign – Telling your story shouldn’t be a solo mission. Empower your team (teachers, parents, etc.) to help showcase the work you are doing. By sharing the vision and engaging others in the work, we extend the influence of our story and build organizational capacity and buy-in for sustaining that work.

- Not Just a One-Time-Thing – Telling your school’s story isn’t an event, but a process. Like learning itself, our story is something that needs to be developed, cultivated, and honed over time through consistent practice and reflection. An inspirational tweet is just that – inspirational. To tell your story, you need to be focused on the ongoing, consistent “telling” of your story. If you want it to stick, you need to stick with it.

Innovation is hard work, but it’s even harder when we don’t know the root of the problems we are facing. George Curous says that the three keys to innovation are “relationships, relationships, relationships.” I think he’s right. Learning and innovation are social, human endeavors. More than anything else, innovation in schools isn’t about a leader with answers. It’s about a leader who knows how to keep asking questions, and how to inspire others to engage in the work of change. Consider what really underlies our lack of innovation in schools, and then lets roll-up our sleeves to fix it!

Stay hungry my friends.

-Aaron

Thanks for the motivation amigo! Keep it up!

With high hopes,

Adam Foster Carlin

Principal

Sessions Elementary School

2150 Beryl St.

San Diego, CA 92109

(858) 273-3111

acarlin@sandi.net

[Image result for ca distinguished school][Kate Sessions Elementary School in Pacific Beach San Diego]

LikeLike