To me, AI is a little bit like Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour: It’s everywhere. It’s all the time. There is probably something good there, but honestly, I’m just tired of hearing about it. Yet, here we are. It’s a brave new world, and it would appear that AI is here to stay. So what now?

If your school or district is anything like mine you are likely engaging in conversations around how to “handle” AI. Specifically, much of the conversation tends to focus on the concerns around “cheating” and methods for assuring that students don’t use AI to cheat on their work. To be sure, parameters and guidelines are important for ensuring that students are safe and policies are fair and consistent. However, the near total focus on the application of the tool highlights a blindspot I see too often with education leaders. Namely, we approach the problem as managers rather than leaders.

Simon Sinek has provided a number of helpful descriptors highlighting the difference between “leaders” and “managers,” but perhaps my favorite is this: Managers reward compliance, while leaders reward dissent. If we transfer that thinking to the conversations we tend to engage in around AI, the parallel becomes a bit more clear. We are focused on developing rules, policies and guidelines focused on compliance. We want to manage AI.

But what if we took a step back, and as leaders attempted to dig a bit deeper? Is it possible that AI is the proverbial push we need to confront the truth that we have ignored for far too long – that most of what we teach doesn’t matter nearly as much as we think it does in a world where knowledge is ubiquitous and always accessible. Maybe the problem isn’t kids cheating, but rather that what we are asking them to do is so low level that AI can do it just as easily. Maybe the answer to how to “handle” AI lies in our own willingness to think bigger about what type of work matters for students. As the late Sir Ken Robinson once said, “The issue is not that we set the bar too high and fail, its that we set it too low and succeed.” We can do better, and if we are serious about preparing our kids to be successful in the future, we must.

So where should educators start as they consider shifting the goalpost and raising the bar beyond basic knowledge acquisition? Consider these four ideas a possible places to start.

1) Consider the Psychology of Motivation

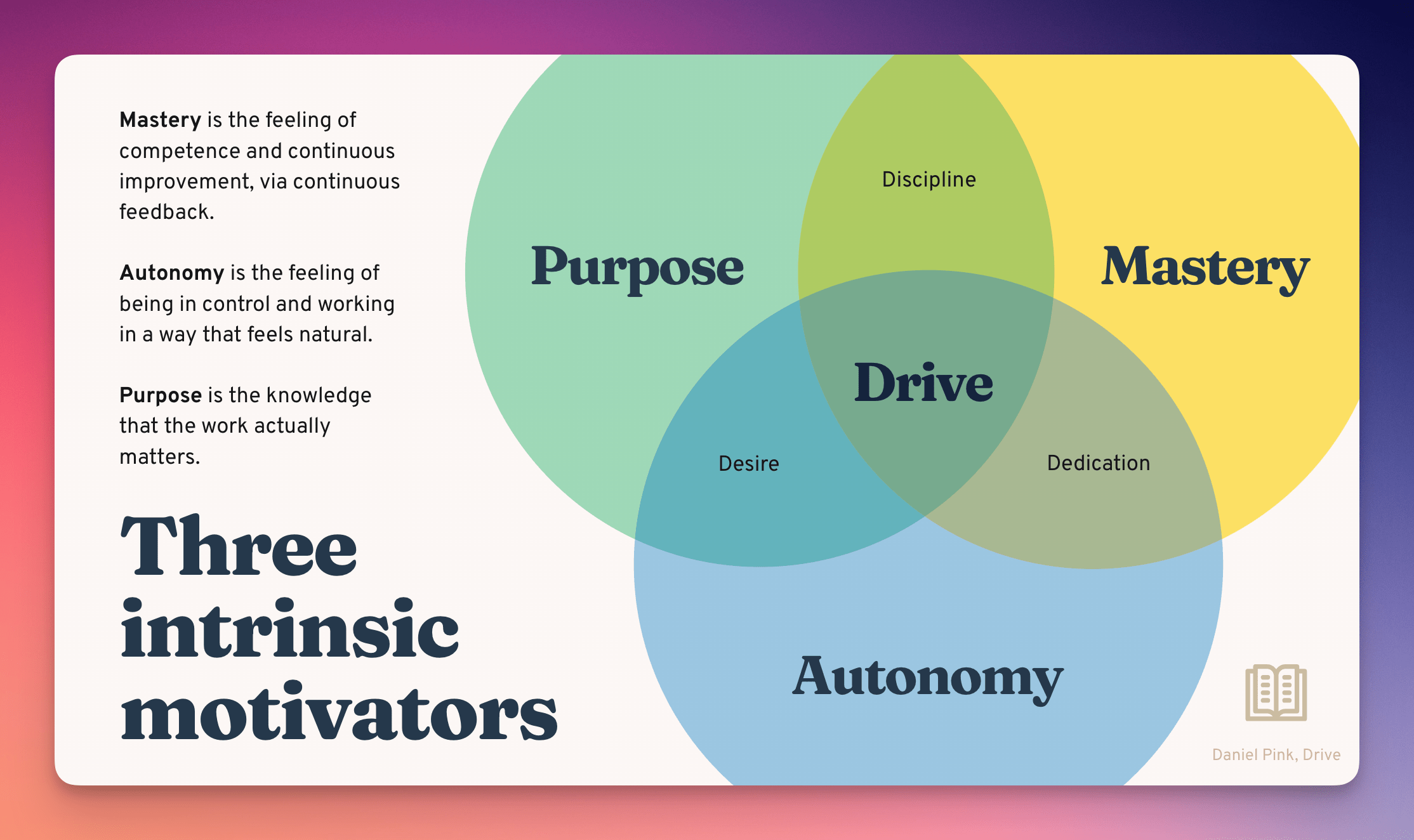

Perhaps the best way to think about planning instruction for students is to start with considering the psychology of what motivates. Self Determination Theory (SDT) has been well researched over many years, and it has been couched in different terminology. Yet despite that, the concept remains the same. As Daniel Pink phrased it in his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, the three critical components of motivation for all people are autonomy, mastery and purpose. Students need exposure to tasks that provide them agency and autonomy to approach the work in ways that make the most sense to them. They need to focus on improvement and mastery rather than an arbitrary grade or score. They need to see purpose in their work beyond the walls of their classroom or the score in the gradebook. A motivated learning will want to do the work themselves rather than outsource it to AI.

2) Consider the Conditions for Powerful Learning

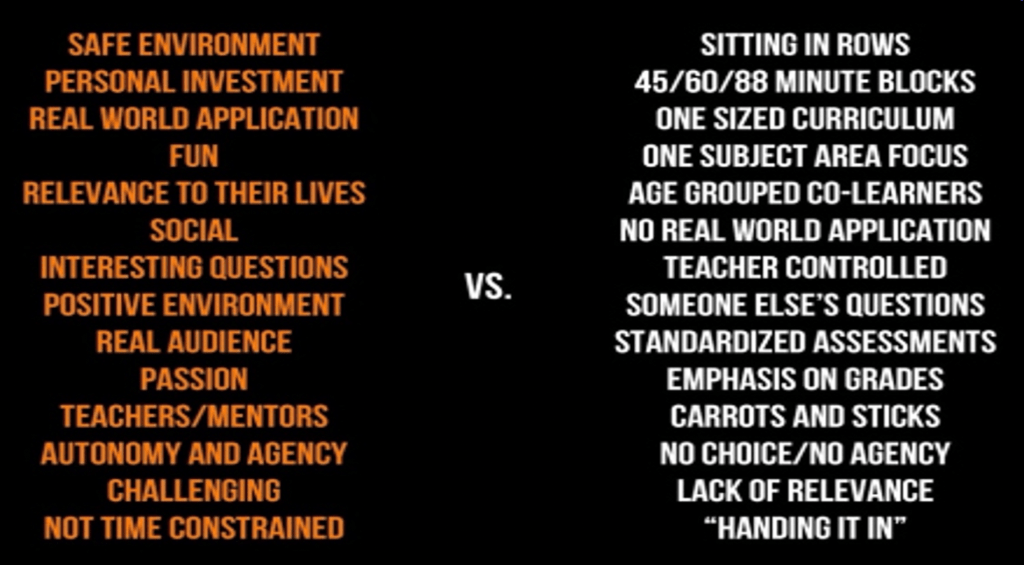

In his book, “Freedom to Learn,” Will Richardson talks a lot about the conditions for powerful learning. Specifically, he focuses on the disconnect between the way we approach meaningful learning in every aspect of our lives, and what we structure the learning experience to look like at schools. In a TED talk he provided the visual below:

Will uses this visual to showcase some of the elements of deep, meaningful learning (social, not be constrained by time, real audience, real world application). As he states in his TED Talk, we know what deep meaningful learning looks like because we have all experience it – whether it be learning a language, a new hobby, or a skill. Yet, we rarely construct schools and classrooms around these same principles. Instead, we construct classroom environments that emphasize “teaching” (compliance), rather than “learning” (exploration). So if we want students to be engaged and invested in their work, let’s amplify the characteristics we know lead to meaningful learning.

3) Take Learning Offline

Our students already spend way too much time on devices each day according to research. As a result, we are seeing larger numbers of students than ever before suffering from mental health issues, depression, anxiety, and shortening attention spans. As one technologist put it, “companies are in a race to the bottom of the brainstem – and we are the ones who are losing.” We also know that a side effect of this increased technology use is that students are engaging in less direct contact with the outside world and fewer face-to-face interactions with adults and peers around topics of substance. If we look for opportunities to move our learning into a more dynamic and conversive setting, we may also see less of a need (or opportunity) for the task to be automated by AI. This may also help us to focus on higher order learning, while using AI to help with some of the prep work. For example, rather than have kids write an opinion paper about immigration (easy to do with ChatGPT), engage students in a socratic seminar where they are tasked with engaging in real-time and building off of the ideas and experiences of others. Take a nature walk to study animals and plant life. Explore a local community problem and let kids talk about (and design) possible solutions. Engage students in the type of real work we do as adults – work that is collaborative, problem driven, and creative.

4) Embrace Creativity & Play

While AI is progressing at a rapid rate, one of the areas where AI still struggles is the generation of novel ideas and creative solutions. Since these models are trained on existing information and solutions, novel creation is still very much the realm of the living. Moving a step further, we also know that schools are incredibly good at driving creativity out of students in favor of the “right” answers. What do we get? Demotivated learners who are taught to think like ChatGPT – but less effectively. Talk to anyone in a high leverage career (engineer, tech, biomedical, finance) and they will tell you that when hiring new employees they often have a common, glaring gap – they are booksmart but lack the ability to collaborate creatively to develop unique solutions to abstract and complex problems. That probably isn’t surprising considering that we rarely prioritize the time and space needed for students to develop the skills of creative problem solvers. We focus almost entirely on content without the opportunity to develop the underlying, transformative skills they will need most in the future. So consider letting kids play creatively – design an outdoor learning space, make a Rube Goldberg machine, engage in rapid prototyping and design challenges. Remember, what matters here is not the “content” of what they are doing, but the skills they are developing through the process.

While AI certainly creates some new challenges for educators, it may be the catalyst we need to shift student learning in ways that will make schools the types of spaces that kids and adults want to be – creative, social, rigorous and fun!

*This article was NOT written by ChatGPT.